How Mount Blue Sky got it's Name

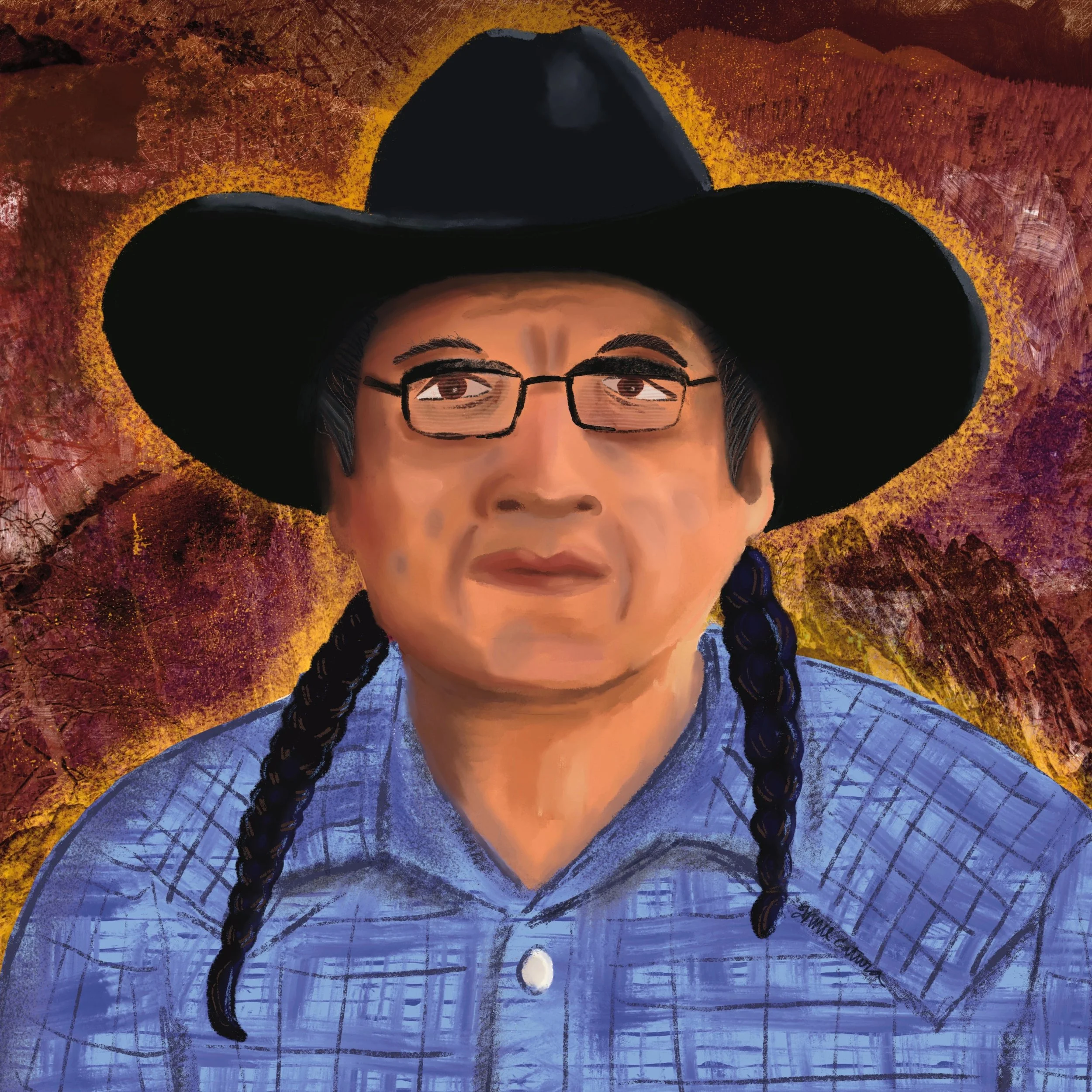

Fred Mosqueda, a Southern Arapaho elder

When Fred Mosqueda, a Southern Arapaho man, spoke in his native language, his words filled the room with a measured resonance — deliberate and poetic, as if each syllable had been carefully placed. The cadence of his speech carried the weight of memory, a lineage of stories handed down through generations. Mosqueda was invited to Evergreen to share his people’s stories as part of “Sacred Spaces,” a community event hosted by the Evergreen Area Chamber of Commerce in recognition of the 150th anniversary of the name "Evergreen." He came to share stories not just from the past, but from a living cultural memory still rooted in the land. He began by offering a brief glimpse into the Arapaho creation story — a story that traditionally takes three days to tell. The portion he shared suggested a world born of water, shaped through cooperation between animals and people and rooted in connection to the natural world. Though the full story remains with the Arapaho people, what he offered felt like a gift — an invitation into a worldview defined by reverence, relationship, and time.

Mosqueda then turned to the story of Little Raven, a Southern Arapaho leader remembered for wisdom and foresight. In Arapaho society, boys entered graduated societies at age 12 to begin learning the language of men and the responsibilities related to the horse. Little Raven advanced beyond his peers and was believed to have a gift for reading signs — even controlling the weather. He foresaw the arrival of white settlers and recognized that survival would require unity. He forged peace among neighboring tribes — including the Lakota, Cheyenne, Comanche and eventually the Ute, long-standing enemies of the Arapaho.

Little Raven was the Southern Arapaho chief who led his people through the treaty years. He used Chief Left Hand as his interpreter, as Left Hand’s sister had married a white trapper who taught her brothers English — a connection that helped Little Raven bridge cultures during a time of upheaval. When the U.S. government imposed a title on him —chief over all Indigenous people in the Front Range — it was not a position he sought, but one he carried with grace. Mosqueda quoted a phrase in his native language that reflects the Arapaho people’s understanding of the land: “My father lives in heaven; the earth is my mother.” The concept of owning land — of owning one’s mother —was inconceivable. Yet, as treaty after treaty was broken, by 1861 the Southern Arapaho and Cheyenne were removed from their homelands and no longer entered the Denver area as a complete tribe.

Still, their traditions endured. When the U.S. government banned the Sundance, the Arapaho found creative ways to protect it — at one point presenting it as a fundraiser in support of American troops, allowing the ceremony to continue under the watchful eye of government authorities. It was an act of quiet defiance and cultural brilliance. Though their language is spoken by few today, oral tradition and song remain —each carrying memory, lesson and prayer.

While the full story of the Sand Creek Massacre is now respectfully told at the History Colorado Center in an exhibit created in partnership with Native tribes, its legacy still lingers. Governor John Evans, whose failure to lead — including leaving the territory during a time of fear and propaganda — was long honored with a mountain bearing his name. For many, that name became a symbol of betrayal. When the time finally came to consider a new name, Fred Mosqueda was asked to propose one — and to do so quickly. The urgency clashed with the measured, communal approach that defines tribal decision-making. After meeting with Cheyenne leadership and voicing concern that the task shouldn’t be rushed due to the distinct cultural identities of the tribes, Mosqueda was walking back to his office when he heard the words “Blue Sky” spoken from the Cheyenne leader’s doorway.

It stopped him. The name resonated — meaningful to both the Arapaho, known by some as the Blue Sky People, and the Cheyenne, whose Blue Sky Ceremony is one of their most sacred traditions. Blue Sky was not a compromise, but an affirmation of identity, memory and shared connection — a name that didn’t erase pain but carried healing. Although the name came swiftly and with quiet certainty between the tribes, its official approval moved at the glacial pace of bureaucracy.

Mosqueda later reflected on the irony: What was thought to be too difficult was spoken aloud and embraced in a single afternoon, while what was deemed politically timely took three years to be realized. Still, he emphasized that the change would not have happened without the people of Colorado — their willingness to listen and to lend their support made reconciliation possible.

Mount Blue Sky is more than a correction. It is a reminder that history cannot be undone, but relationships can be repaired. The Southern Arapaho continue to return to this land to gather medicines and tipi poles. Their presence — like their stories —endures.